On this page...The woollen industry|Why tenter?|Shrinkage|Weather|Wet-houses|Indoor drying|Provision of tenters|Suggested reading.

Manufacture - woollen cloth-making

The Woollen Industry...

The production of woollen cloth is complex, not only in terms of manufacturing practices (see the right column), but also the economic basis. The interrelationships of wool suppliers, spinners, clothiers, fullers, cloth dressers and merchants varied across the country. There were different historical developments and specialisations in the various cloth-making districts.

As a gross oversimplification, within the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in the south of the country manufacture was directed by large-capital master manufacturers who owned the wool, yarn and cloth and employed workers in a range of facilities - domestic, mills and factories. In the north, the clothier with little capital bought and owned the wool and worked the cloth up largely in domestic facilities using families and a few trained cloth-workers (journeymen). He had it fulled by millers, and sold the piece (having perhaps dyed it) to merchants in cloth halls and markets. The cloth was 'undressed' ('balk'), straight from the tenters. The merchant had the cloth finished.

From the fourteenth century, the cloth industry was a very important source of employment and contributed significantly to the economic performance of the kingdom - 'the great staple trade of the kingdom'.

Here is not the place to review these topics when there is a plethora of excellent literature available. At the bottom of this page is a reading list of authoritative academic texts and readable summaries on the industry nationwide.

Dyers washing and draining cloth in the River Calder near Whalley Abbey, Lancashire. JMW Turner,Whalley Bridge And Abbey, Lancashire: Dyers Washing And Drying Cloth, detail.

Why tenter?

Tentering was an essential part of the manufacture of 'woollen cloth' - a textile made with warp and weft of fine carded wool with short non-parallel fibres. Tentering was used to stretch and dry the cloth, principally after scouring and fulling, the latter an essential process that transformed the loosely woven, low tensile strength web from the loom into a consolidated, commercially useful textile with no visible web. It was also a requisite for the subsequent process of raising the nap (projecting wool fibres) and shearing to produce a velvety feel when handled and pleasing to the eye. During the dressing process, the cloth may have to be returned more than once to the tenters. Tenters were also used to dry cloth after dyeing.

Not all woollen textiles were milled and tentered. Worsted, for example, was a tightly spun and woven cloth made from long staple wool, combed to make the fibres parallel. Short fibres ('noils') were removed and sold to the 'woollen cloth' trade. The aim was to present a smooth, fine cloth with an accentuated pattern and an evident web for aesthetic purposes. It was not normally fulled; it was unnecessary and would have toned down colours and compromised the aesthetics (some cloths such as serges containing worsted yarn, usually as the warp only, could be be lightly milled). A known aphorism was: Worsted was perfected in the loom, 'woollen cloth' in the finishing. Plainly, the characteristics of the yarn were also important; for example, worsted was spun and twisted differently from that prepared for woollen cloth.

Fulling produced a more dense 'felted' cloth providing warmth, strength, and a degree of water resistance. It was a prologed, rather violent, wet process employing much soap, scouring, and use of substances such as fullers' earth and stale urine. The design of the fulling stocks promoted mechanical compression, agitation and rolling of the piece for many hours to drive the weft yarns together and felt the cloth. This generated heat which was an important consequence of these processes. There was considerable shrinkage, thickening of the piece, and distortion (the middle of the piece shrank more than the selvages).

Subsequent tentering not only dried the cloth but tenters had the facilities to increase the length and breadth of the fulled cloth to commercial and statutory requirements, remove creases etc., and with patterned cloth, correct misalignments arising from uneven shrinkage.

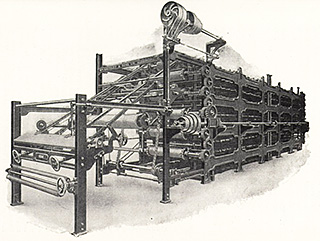

A pulley system fixed to the 'head' to stretch the piece in length; blankets at Witney. Courtesy Oxfordshire County Council - Oxfordshire History Centre. There is a very good website on the Witney blanket industry.

Field tenters were sited outdoors, either singly (usually tens of yards in length) or in 'seams' of generally parallel rows, ideally south-facing, on elevated positions in a field or mill yard. In urban areas they could be placed on spare ground within the built area, for example, alongside canals and roads. Seams were set yards apart on level ground to ensure that in winter months with the low sun, they did not shade each other. On hill slopes, rows of tenters were often placed atop individual small revetments to provide level platforms following the contours (tenter-banks), features that may still be noted today. On hill slopes, the seams could be set closer together without shading adjacent seams in winter.

Field tenters were employed prior to the early medieval period. They still had a role outdoors after tentering started to move indoors in the mid-nineteenth century factory system, employing heated covered tenter sheds (stoves) and tentering machines (stenters), largely to avoid the vagaries of the weather and improve throughput. Outdoor tenters persisted into the 1950s in the blanket industry. They no longer grace the landscape.

Shrinkage - why, and how much?

Weaving introduces tensions into wool fibres. Further stresses induced by stretching and drying wet cloth on tenters introduces a temporary 'set'. These tensions are released irreversibly if the cloth is thoroughly wetted passively (relaxation shrinkage), the cloth contracting to inherently stable dimensions. Cloth was normally fully wetted before being stamped with its formal dimensions as required by law in some time periods. Woollen cloth shrinks irreversibly when mechanically agitated during milling/fulling. The shrinkage arises principally from the presence of scales on wool fibres. There is a greater resistance to fibre movement, relative to an adjacent fibre surface, when moving it towards the tip rather than the root i.e. greater friction stroking from tip to root than the reverse (the 'Directional Frictional Effect'). Repeated compression of the piece in the fulling stocks forces the fibres together to entangle. The differential friction longitudinally due to the scales leads to migration towards the root, but the scales also limit the recovery from the motion (wool fibres are elastic), and rather like a ratchet, it leads to contraction of the piece. Factors such as fibre elasticity, yarn structure, weave density, temperature, pH, and lubricant type will modify the ultimate degree of felting, its progression, and the magnitude of the shrinkage.

Woollen cloth came in many forms and developed over the centuries in manufacturing approaches and fibre characteristics, driven by commercial and aesthetic requirements. Therefore, the magnitude of cloth shrinkage after fulling was variable. In 1842 Bischoff (Ref. 1) gave a generalized figure of a reduction in width by 40-45% and in length by about 50%. Brooks (Ref. 2) noted that Wiltshire broadcloths when milled 'doth shrink from what it was set in the Loom, to what it doth contain, when finished, about one half of its Breadth, and about one third of its Length'. In 1502, coarse Norfolk broadcloth was woven to accommodate a 36 percent reduction in width after milling to meet the statutory width requirement (Ref. 3). In Miles' 1840 report to a Royal Commission on the condition of the hand-loom weavers in Gloucestershire, a broadcloth 3 yards in width and about 54 yards in length in the loom was reduced in size by 42% and 26% respectively when milled (Ref. 4). Employing modern processes (1977), Brearley and Iredale calculated averaged 10% reduction in length and 20% in width in a 'standard woollen finish' (Ref. 5).

Weather

Joseph Holroyd, a cloth factor buying in Halifax for customers in London and Flanders (via Hull) bemoaned problems with weather in letters to customers in 1706-7 (Ref. 6). For example: a Mr Dorpere buying ninety 'Bayes' (worsted warp and woollen weft) was told 'I hope to send them towards Leeds tomorrow if a fair day, for there is 7 or 8 pieces on the Tenters, wee have had much rain has hindred the drying of them' and 'the bays are yet on the tenters, as soon as dry and ready yow shall have Invoice of them'. Similarly to a Mr Bollinger '…we have had very bad drying'.

Clothier Samuel Hill also shipped to London and Hull for Antwerp; letters in 1737 to a customer stated '…we have had so much rain and Snow' and to another '…as soon as we have Sun and the fine weather comes on I shall have 25 Samuels I think the Best I ever made'. To a Mr Verbeck he wrote 'I here enclose you Invoice of 1 Bale Kerseys which I wod have sent sooner if possible cud, but we have had so much rain and Snow upon these Hills that we cud scarce get anything dry. this Bale is not yet ready'.

In 1760, John Brearley of Wakefield, a cloth frizzer (finishing cloth with 'knobs and curls' on the nap) wrote in his memorandum that 'In and about Wakefild itt is chiefly drye fair wether oftener dryeing tenters in the winter season then in and about Hudersfild or Saddleworth or aney where in and about Rochdale. Perhaps sometimes dryes two days in a week when the above places cannot drye one wich makes Hudersfild matkitt [market] scarce of cloath them times' (Ref. 7).

It is interesting to note that in 1772, Brearley, recognising the difficulties of drying cloth in the winter quarter on field tenters, sketched a design in his notebook for adjustable tenters for broad or narrow cloths that could be used in a house: 'Now you may Fix 4 or 5 of these tenters in a Room to Drye them with have 4 or 5 Great iron pans in ye room with ye Mouth Downwards so Kindle a Fire under them and ye Smook to Run up a tunill so into your Chimney itt goes have and iron Door to your iron pans'. Having dry cloth could have a price advantage in cloth markets when other clothiers were struggling to get their pieces dry. Indoor heating did not emerge in Yorkshire until the early nineteenth century; Brearley was considering domestic approaches in the 1770s (Ref. 8, Ref. 9).

Overdrying by say leaving the cloth in full sun was generally avoided if further processing was scheduled. It also gave the cloth a glazed appearance. Cloth on tenters may be 'dewed' by leaving it overnight to absorb atmospheric water, or taken off the tenters and laid on the ground to absorb a little water naturally. This facilitated finishing, and improved the feel of the cloth ('handle') before sale.

Wet-houses

A 'wet-house' was a building close to or within isolated tenter-fields, in which cloth could be temporarily stored either before mounting on tenters, or used as a shelter for cloth removed from tenters in foul weather. They could also be used for storing winches, ladders etc. Very few such buildings have been formally identified, with the best remaining example in Lancashire at Stubbins Vale Mill, near Ramsbottom, Lancashire. Inspection of nineteenth century OS large scale maps does occasionally reveal a building in an isolated commercial tenter site, such as in a tenter-field at the top of a steep-sided valley to catch the sun and breeze, the mill sheltered at the bottom associated with the water flow. Prompt removal of drying cloth in changeable weather would take some time; the wet-house enabled quicker access and nearby storage facilities. Wet-houses were also used for associated wet processes such as 'bluing' (to whiten cloth).

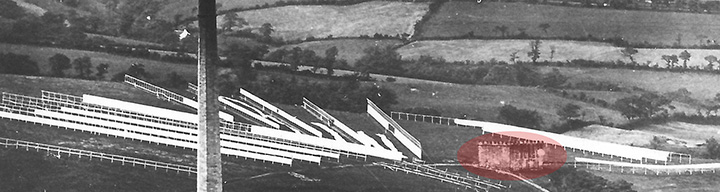

Stubbins Vale tenters and wet-house (shaded oval) on a photograph taken in the 1870s. Note that the castellated wet-house was originally a single storey as shown here, but shortly after this photograph was taken it was raised to two storeys.

In this period, Porritts and Spencer's Stubbins Vale Mill near Ramsbottom made lappings (linen warp and worsted weft) and specialised blankets, both used in the calico printing industry to wrap the engraved rollers. The wet-house was built in the 1860s and is now owned by the National Trust (described as an 'eye-catcher'; it originally had a flag-pole). It is 35 m above the mill in the Irwell valley below, located on the edge of the elevated tenter-field.

Three kilometers to the north was Sunnybank Mill, owned at one time by the same family, that had a very similar wet-house built around the same time some 21 m above the mill, again on the edge of an elevated tenter-field. By 1927, all the tenters were indoors in a long tentering room. This wet-house tower was demolished in 1988. (Information on the two mills courtesy of John Simpson, Helmshore).

Left - The outstanding castellated Stubbins Vale Mill wet-house. Right - Sunnybank Mill wet-house in the 1960s (shaded), with the old tenter-field at the top of the photo. Courtesy John Simpson, Helmshore.

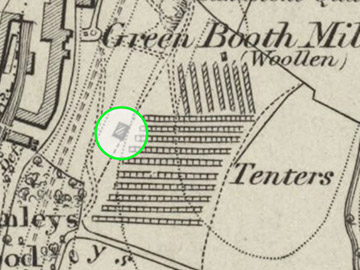

The tenter-fields of Greenbooth Mill (left, SD85761557) and Ashworth Mill (right, SD85521354), both in Rochdale, had buildings near the racks, undoubtedly wet-houses. Both tenter-fields were high above the mills, on a plateau. The maps are First Edition 6 inch surveyed 1844-47/48.

Greenbooth Mill is now submerged beneath a reservoir, but its tenter-field 38 m above the mill remains to this day as pasture, high above the water level. There is no evidence of tenter remains. A few random stones built into a low wall remain where the wet-house was sited (it was demolished before 1910). The mill also had a two-storey indoor tenter dry-house 60 yd long and 7.5 yd wide (Leeds Intelligencer, 23 Jan 1847).

Indoor drying - stoves

In 1856 there was a local festival at Dockwray Hall Mills in Kendal (now in Cumbria) to commemorate the success of the local manufacturers at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, 1855 (Ref. 10). Eight hundred people attended the festival in a mill. A play was performed, written by a dyer, Thomas Thwaites, and in one scene it extolled the speed of newly-introduced 'stoving' over field tentering for drying cloth. The plot was that a cloth was needed in London the following day:

'steam's well up for t'stove, or t'll nivver be done. If it had to be tentered on't fell, for aught I see it mud be a month afore it were dry, instead of four or five hours in't stove'. [Harking back to the good old days though], '... its baith pleasenter and healthier to have a good blow on t'fell, t'feel t'sun warm on one's back ... than to stick forever between two walls and a steam pipe.' [Fine in summer, but in winter snow ...], 'setting unjoint tenters ... fingers starved [extremely cold] ... till we were right fain [pleased] to get home.'!

Air dry-houses, dating from the late eighteenth century, were naturally ventilated with wall openings and a roof, but were not common in woollen mills. They persisted into the nineteenth century for the drying of linen (Ref. 11). There is a former air-drying house (now converted to offices) in Exeter at Cricklepit Mill, with tenterhooks still embedded in some beams. Covered tenter frames sheds were also employed in some of the Isle of Man's woollen mills. A single delapidated example remains (Ref. 12).

Heated 'dry-houses' were long, narrow buildings to accomodate full cloth lengths, having small windows and roof vents. They were often multi-storeyed, and were introduced early in the nineteenth century. At Benjamin Gott's Bean Ing mill in Leeds, the daily notebook declared 'Pieces were tentered in the Top Room of the Dryhouse on Monday Evening, Decr 5th, 1814 - this being the first time of its being used' (Ref. 13).

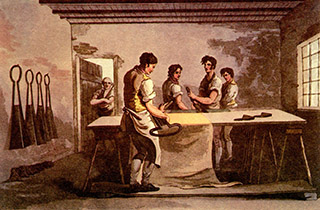

Indoor tentering at Wikes Mill, Bury, Lancashire in 1976. Left - mounting woollen cloth used in the paper industry on 'double tenters' where the cloth is mounted both sides of the rack over the 'saddle' at the top. Right - Cloth fully mounted. The heavy cloth was pulled taut into position in the long shed using a 'crane' (a winch). Courtesy Ken Howarth, Heritage Photo Archive.

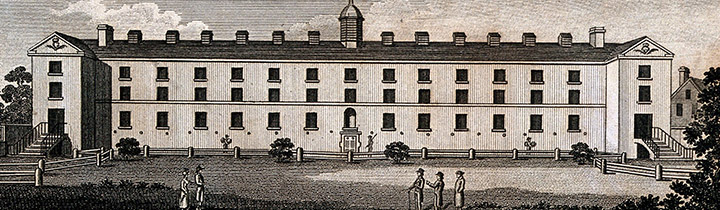

Stove tenter house, Dublin

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, 18,000-22,000 people in Dublin were supported by the weaving industry. Poor weather had a profound impact on the production of cloth leading to poverty; tentering was seriously curtailed. Weavers and the principal clothiers made a case (a 'Memorial') to then Earl of Meath, Lord Mayor & Aldermen, who in turn made a case to the Dublin Society for a 'large stone tenter-house' to be built (Ref. 14).

'In the winter season, when rains, snows and frosts set in they are all thrown idle; neither the wool, warps, nor cloths can then be dried ... Hunger and cold are succeeded by divers disorders, which break up their little families, and many of them are obliged to seek relief in the public hospitals, infirmaries and the streets'.

The need was supported and approved by the city fathers. There were delays in implementing the plans so local businessman and philanthropist Thomas Pleasants provided full financial support and started work on 14 Apr 1814. It cost over £14,000. There were four 'stoves' in the basement, iron gratings to disperse heat, three floors with tenters on first two, and wools and warps on the top floor.

'Tenter House with grounds, Dublin, Ireland', line engraving by B. Brunton, 1818. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection; Public Domain Mark, Creative Commons. Cropped.

From September 1816 to December 1817, 1683 pieces of cloth, 2096 warps and 1870 stones (11,875 kg) of wool were sized, dried, tentered and finished. The Stove Tenter House 'caused want and idleness to disappear with all their concomitant miseries'. Hand weaving eventually declined and in 1855 it was used as a night refuge for homeless women and children (Ref. 15). It is still standing in Dublin today.

Provision of tenters

Tenters were traded and rented like many pieces of manufacturing equipment. For example, John and Thomas Clark of Trowbridge were a firm, established in 1680 of medley and Spanish merino cloth makers, and were wool dyers. They were employers of spinners and weavers over a large area. In 1804 they possessed one tenter 42 yards long for Cassimeres (twilled cloth, printed or dyed), but rented other tenters. In 1816-18 they bought a new 44.5 yd rack for £13, and three more from two other dealers. In 1828-9 an iron rack was purchased new for £27 10s, and four second hand for £28, with additional costs for iron supports and erection (Ref. 16).

Clothiers

Domestic clothiers in Yorkshire provided or rented their own tenters to dry fulled cloth before sale at markets. John Dickson and Mary his wife of Lepton, Huddersfield, gave licence to their clothier tenant Richard Hanson of Wakefield, to set up and use two pairs of tenters for the tentering of woollen cloth outside the dwelling. He could proceed with with the tenters in the croft (the land around the house) providing the tenter ground was not larger than 20 x 20 yd square, and within 20 yd of the building. The 'consideration' was £100 with a peppercorn rent (Ref. 17).

Common land and inclosure

Some public bodies provided space for the erection of tenters. Unenclosed common land was used to undertake tentering and other associated woollen processes such as warp stretching and drying. These encroachments were usually unauthorised. The enclosure of commons close to developing woollen manufacturing towns such as Leeds led to threats to the clothier's use of these sites. Cloth manufacture was an important employer and of economic benefit to the area, facts recognised by the more enlightened commissioners and freeholders. Around Leeds, unenclosed lands at Armley, Wortley, Bramley were used for tentering (Ref. 18).

The Inclosure Acts for Armley and Wortley near Leeds are exemplary examples, and still - in some cases - providing public benefit today for recreation. The Act to enclose Armley was passed in 1793, with the Award in 1799. Recognising the requirements of the clothiers, the Commissioner stated:

'I do hereby set out and allot eight acres and half of the said Commons and Waste land ... which are as near as can be to the several [clothiers'] cottages ... erected upon or adjoining to the said Common or Waste Grounds and which shall ... for ever hereafter remain open and unenclosed ... setting up and using of Tenters, stretchers for Warp Wool, Hedges for the spreading and drying of wool or for any other use ... under such Regulations as the Minister Chapel Wardens and Overseer of the Poor for the time being ... shall from time to time for ever hereafter approve ...' [list of 11 allotments followed ranging from 14 perches to 3 acres 1 rood 4 perches].

The Award also stated that there should be 'no roads, footpaths, properties, trees, or other obstruction may be on or near the Tenters' Ground' (Ref. 19).

Some of these sites remain open areas to this day; the Armley Common Right Trust manage six sites, the most prominent being Armley Moor.

The Armley tithe apportionment, (21 Feb 1845, IR 29/43/17) shows that 'Armley Township Churchwardens and Overseers of' owned eight 'Privilege Grounds' for tentering etc., (plus a Pinfold, School & Yard, School Close and an Allotment). Currently, five of these sites are still open areas in urban Armley, three are built over.

Also in Armley was the 'Conveyance of a parcel of Land at Armley for the purpose of Tenter Ground' (WYL744/12) dated 25 February 1836. There was an indenture between Benjamin Gott of Armley (woollen industrialist and former Mayor of Leeds) and the Minister, Chapelwardens and Overseers of the Poor of the Township of Armley (Rev. Clapham, Minister, two chapel-wardens of the Township and Chapelry of Armley, two clothiers, and a Gentleman). Gott was paid £150 by the Church-wardens and Overseers to purchase the land, to be used tentering etc.

There was similar provision in neighbouring Wortley (Inclosure Act 1833, Award 1847). There was some opposition to the inclosure. In the Leeds Times (25 Apr 1833), 'Freeholders and inhabitants' were seeking compromise over the inclosure. Freeholders were determined to go ahead, in the knowledge that it would be expensive for inhabitants to oppose the bill in Parliament. They came to an agreement concerning clothiers' requirements. The Act would go forward, but about 3 acres of the nearly 40 acres of common 'shall be kept open for the purposes of tentering &c.'. The locations and size of portions were agreed; they were vested in church-wardens and trustees. Use was for 'tentering Woollen Cloths, drying Webs and spreading Pieces thereon and for other such Uses and Purposes' (Leeds Mercury, 30 Jan 1841). On the Tithe map (dated 2 Sep 1846) were the six 'Privilege Grounds' owned by 'Wortley Township' (plus two more , Workhouse Croft, and Wortley Chapel and Garth). Of these six, currently two are built over, two are open areas, one is partially built over, and one a grassed area in school grounds.

Suggested Reading

Bentley B, 1970, The Pennine Weaver: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day. [A good, simple introduction, very readable, excellent illustrations.]

Mann J De L , 1987. The Cloth Industry in the West of England: From 1640 to 1880.

Heaton H, 1965, The Yorkshire Woollen and Worsted Industries: From the Earliest Times up to the Industrial Revolution, Second Edition.

Wild M T, 1972, The Yorkshire Wool Textile Industry in J Geraint Jenkins, 'The Wool Textile Industry in Great Britain'.

Harte N B, Ponting K G, 1973, Textile History and Economic History: Essays in Honour of Miss Julia de Lacy Mann.

Lipson E, 1943, The Economic History of England. Vol. II, The Age of Mercantilism, Third edition.

Lee J S, 2018, The Medieval Clothier.

Oldland J, 2016, The Economic Impact of Clothmaking on Rural Society, 1300-1550 in Allen M, Davies M, 'Medieval Merchants and Money: Essays in Honour of James L. Bolton'.

Marsh J T, 1947, An Introduction to Textile Finishing.

Brearley A, Iredale J, 1977, The Wool Industry.

Ponting K G, 1970, Baines's Account of the Woollen Manufacture of England.

Crump W G, 1931, The Leeds Woollen Industry 1780-1820.

Oldland J, 2021, The English Woollen Industry, c.1200-c.1560.

Satchell J, 1984, Kendal on Tenterhooks.