On this page...Developing quality standards|Local controls & guilds|Deceits in cloth-making|Individual Acts|Crime.

Statutory Control

Developing quality standards for woollen cloth

The woollen industry was 'Parliament's spoilt child' with regulations and laws to guarantee the quality of the product and to raise profits. The trade employed pressure to legislators to make Statutes that would support its actvities, and resist efforts to moderate existing laws (Ref. 1).

In 1791, there were 307 laws on the Statute book regarding yarn production and woollen cloth-making. They addressed such practices as clipping of sheep, length, breadth and weight of cloth, materials for dyeing, fulling, and controlling tentering practices. A 1622 commission declared 'the laws now in force concerning the making and dressing of cloth are so many and by the multitude of them are so intricate that it is very hard to resolve what the law is' (Ref. 2, Ref. 3).

From the High Medieval Period, there was local control through the 'guilds' and 'companies' of towns and cities. The earliest statute was the 1197 Assize of Measures.

Women making woollen cloth, depicted in a c. 1150 manuscript - the Eadwine Psalter. There appears to be weaving on an upright loom, two women with shears (and sheep, with a shepherd blowing his horn), and a woman preparing yarn for the loom. From The Eadwine Psalter, f.263r, c. 1150, The James Catalogue of Western Manuscripts. Copyright the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0.

Local controls & guilds

A guild was originally a collection of freemen that managed the affairs of a town - a fraternity of 'brothers'. They developed into organisations that controlled trade in the town, ultimately specialising into 'craft guilds', such as weavers, fullers, butchers etc. Their aim was to maintain standards in their craft and trading arrangements both internally in terms of mutual support in issues such pricing, and their interplay with other towns. Apprenticeship was strictly controlled to ensure good quality work, and there were requirements to undertake agreed technical practices to maintain standards and mutual benefits to 'brothers' and the well-being of the town. The large expansion of cloth exports in the medieval period, entrepreneurship and diversification of the cloth trade within the England eventually led to their demise. But some 'companies' continued local control of standards into the sixteenth/seventeenth centuries, or even later in isolated cases.

For example:

'that thenceforth no freeman of the City [London] sell any woollen cloth by retail or otherwise, except by one yard and one inch to the yard, without fraud, &c'. And 'Also that no freeman occupy any tenters for planing woollen cloth without the liberty of the City, and that all tenters within the liberty should be destroyed after Christmas next except ten, five of which should be at Fullers' Hall and five at Leadenhall, and that such tenters should be under the management of discreet men chosen by the Mayor and Aldermen. Also that every freeman have liberty until Christmas next, and no longer, to plane his cloth, notwithstanding an Act formerly made thereon, so that the said cloths be sealed with the seal assigned therefor' (Ref. 4, Ref.5).

The prohibition of tenters other than ten under the control of 'discreet' men at Fullers' Hall and Leadenhall would reduce the risk of cloth on tenters being stolen.

In Newcastle, there were twelve companies called 'Mysteries'. In 1477, the fullers and dyers company required:

'no brother should strain cloth upon the tenter to deliver it with the short wand [a measuring rod], on pain of forfeiting four pounds of wax: nor tenter cloth on a Sunday, nor wend [journey] to the walk mylne [fulling mill] with any raw cloth [not fulled or dressed] on that day on pain of forfeiting two pounds of wax. (Ref. 6).

The wax was for candles used on company processions and ceremonies.

'The Witney Blanket Weavers' Company' (the local guild) controlled many tenters to ensure good quality tentering with no overstretching, but fullers did own racks and finished the blankets for the weavers. (Ref. 7, Ref. 8).

Further reading: In 1887, WJ Ashley published an authoritative discussion for the American Economic Association, on the early English guilds in the woollen industry. (For modern reprint,see Ref. 8b).

Deceits in cloth-making

It is worth reviewing some of the contemporary views from officials and others of the abuses practiced in the woollen cloth industry.

Hugh Latimer, former Bishop of Worcester and firebrand chaplain to King Edward VI preached before the king in 1549 invoking the deceipts of the cloth industry (Ref. 8a).

'Cloth-makers should become Apothecaries? Yea, and as I hear say ... they have professed the gospel and the word of God most earnestly of a long time? See how busy the devil is to slander the word of God ... If his cloth be seventeen yards long, he will set him on a rack and stretch him out with ropes, and rack him till the sinews shrink again, while he hath brought him to eighteen yards. When they have brought him to that perfection, they have a pretty feat to thicken him again. He makes me a powder for it, and plays the Apothecary, they call it flock-powder; they do so incorporate it with the cloth, ... O that so goodly wits should be so ill applied; they may well deceive the people, but they cannot deceive God ... these mixtures come of covetousness. They are plain theft.'

John Leake was one of five London searchers supporting the alnager (official inspector of cloth size and quality). In 1577 he wrote:

'Nexte they stretche and strayne without conscience, not only to make them conteine the lengthes that is appointed, but linger by iij, iiij or v yards; and this is an abhominable falshood. And euen as they deale in length, so do they in breadth also. And here note the great allowance allredy graunted by the statute of 5. E. 6., in the which eury Clothier may straine a yard in length and di. [one half quarter] of a yard in breadth, which might suffice any reasonable persons, if ether the lawes of nature politicke, or of god were in them; but greediness of gayne maketh the honestess of them Corrupte in this behalf. The excuse is: Well, saith the Clothier, the merchaunte must haue great lengthes, or he will not buye; if I sell not, I must put of my spinners and workefolkes, and then what Common wealthe will this be?' (Ref. 9).

In 1613, a deputy alnager John May, wrote:

'In our owne Countrie, where much of our wooll may bee vented [sold], the falshood of clothing is so common, that euerie one striueth [strives] to weare any thing rather than cloth: if a gentleman make a liuerie [livery] for his man, in the first showre of raine it may fit his Page for bignesse, and for the colours and other conditions in it, after a moneths wearing, it will looke like a souldiers [soldier's] coat which hath line sixe moneths out of garison.'

His complaint was that the cloth condition after a month was as if soldiers had been operating and sleeping in the field wearing it for six months!

In 1638-9, Commisioners for Trade were instructed to enquire into the state of the clothing industry (Ref. 10a). In 1640 they concluded that the causes of the 'decay of the trade' were:

- Export of wool, yarn, fuller's earth to foreign countries.

- High price of cloth in the clothier's hands, and of dyeing materials.

- High import duties of English manufactured cloth in foreign countries, enabling them to 'undersell' English textiles.

- The continuing use of 'gig mills', newly introduced to finish cloth; they could produce damage to the piece and caused official concern and were suppressed by law.

- Frauds in manufacture, especially 'streyning' to stretch cloth beyond legal safeguards.

- Deceitful practices by officials such as searchers and alnagers.

Recommendations were proposed for each, also including a 'Crown Seal' for the main 60 clothing towns to pay for officials that could supervise the trade and vouch for quality when sealed, with a mercantile court for disputes.

Individual Acts

The earliest is the Assize of Measures, 20 Nov 1197 (Ref. 11):

'It is established that woollen cloths, wherever they be made, be made of the same width, to wit, of two ells [duabus ulnis - about 36 inches] within the lists, and of the same good quality in the middle and at the sides. Also the ell shall be the same in the whole realm and of the same length and the ell shall be of iron.'

The Articles of the Barons (an agreement between King John and a number of barons), article 12 in 1215, states:

'The measure of corn and wine, and the widths of cloths and other things, are to be reformed; and weights likewise' (Ref. 12). [And in June 1215], 'There is to be one measure of wine throughout our kingdom, and one measure of ale, and one measure of corn ... and one breadth of dyed, russet [a coarse cloth used by the poor] and haberget cloths [a woollen cloth favoured by the elite (Ref. 13)], that is, two ells within the borders; and let weights be dealt with as with measures.' (Ref. 14).

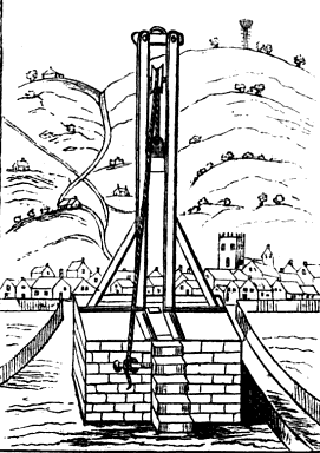

Worth summarising in some detail is the first statute, from 1483, aimed specifically at controlling cloth quality and tenter use (Ref. 15):

Formerly the country has been enriched by the true making and dyeing of cloth and a good many people have been employed. Cloths lately are ‘unfit and deceivably made and wrought keeping neither reasonable length or breadth’. Wet shorn cloth has been set upon tenters and drawn out in length and breadth, some cloths of length 24 yards have been stretched to 30 yards and in breadth from 7 quarters (1¾ yards) to 2 yards and if wetted when dried and strained will shrink when re-wetted.

Flocks and chalk are used to deceitfully improve coarse and white cloth for sale. Every broadcloth should be fully wetted before sale and be 24 yards and an inch per yard, and 2 yards in breadth. Seals of lead should be used for every city, town and county where cloth is made. Cloth shall not be stretched by tentering (or otherwise) ‘after it be fully wett’, or deceitful additions such as chalk. Shearmen must fully wet cloth to be sheared.

‘Please it also your noble grace ... in eschewyng of the greate untrueth and disceyte the which hath grown and daily growth by meane of Teyntours … that no psone … keep, have or occupye any Taynto’ or any other thing in his owne howse or dwellyng place whereby Wollen Cloth may in any wise be drawen out in lenght or brede … But that all Tayntours which hereafter shall be used or occupied, for evenynge of Cloth onely after it cometh from the Mille and before it be roughed & for noon other cause ... be sette in open places and mayors, bailiffs and governors in London, all cities, towns and villages of the realm diligently overse that all Clothes that shalbe sett on Tayntours be not drawen oute in length nor brede'.

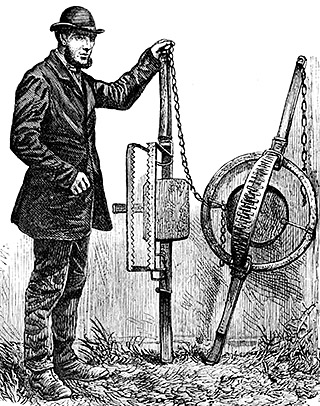

In practice therefore, to constrain stretching and inhibit other poor practices, tenters must be set in open places where they may be observed and inspected. Plainly, this raised the risk of theft and damage to cloths.

For more detail, collections of Statutes by monarch and regnal year are available here:

- Statutes at Large - Wikipedia. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Statutes_at_Large).

- Statutes of the Realm - Hathi Trust Digital Library. (https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/012297566) Great Britain. (18101828). The statutes of the realm: Printed by command of his majesty King George the Third, in pursuance of an address of the House of Commons of Great Britain. From original records and authentic manuscripts. London: Dawsons of Pall Mall.

Privy Council annoyed...

An Act in 1597 (39 Eliz. c. 20) against the deceitful stretching of 'Northern Cloth' noted in its preamble that

'Northern Cloths and Kersies do yearly and daily grow worse and worse and are made more light and much more stretched and strained...to the great deceit of all nations...and to the great slander of the country ... no person...shall stretch or strain or cause to be stretched or strained [list of cloths] made within the said county of York Lancaster or any other counties north of the Trent'.

This was a frank prohibition of tenters and devices to stretch cloth north of the Trent. Tenters were to be removed.

The tale can be followed in Ref. 16. In summary, plainly, this act was widely ignored. The Privy Council wrote to Sheriffs and Justices in Yorkshire, Westmorland and Lancashire. They pointed out that the French king declared English cloths confiscable that have been tentered/stretched, made of two wools, rowed, cockled (not smooth) and stuffed with flocks (that disguised serious defects). Justices had neglected the due execution of the law and were to be called to account. Lancashire replied that it was 'not convenient that the tenters should be plucked down and defaced'!

The French lifted ban the in 1606 and an Act passed in 1623 permitted limited stretching (21 James 1 c. 18).

Legal actions and orders did occur in the interim period; for example in Lancashire Quarter Session Rolls (Ref. 17):

- (Manchester 11 May 1603) Jeremy Wolstencrofte, fuller, at Midleton parish stretched a piece of cloth on a tenter with a lower bar, contrary to the statute. He also assaulted John Fitton and James Hopwood, the overseers in this matter, and rescued the piece of cloth from them;

- (Manchester 29 April 1601) Orders: From henceforth there shall be no stretching of cloth of the length at all with any engine, and all tenters of this hundred shall be pinned and made fast by the fullers at or before Saturday come sevennight so as no stretching of the breadth at all shall be above 3 inches;

- (Preston Orders 8 July 1601): The lower bars of all tenters shall be taken away by the owners thereof and the overseers already appointed, within 14 days next.

Domestic cloth-making. Left - A weaver's cottage above Heptonstall showing mullioned (split) windows to bathe the cottage and loom-shop with light. Right - a derelict weaver's cottage with similar windows and also a 'taking-in door' (centre) on the rear of the house with elevated ground nearby, for yarn etc. to be delivered direct to the upstairs loom-shop, and the piece from the loom to be removed. New Nook (SD95791415) close to Longden End mill, Rakewood, Rochdale.

Parliamentary reports

An 1806 Parliamentary report on woollen cloth manufacture in England (Ref. 18) provides some remarkable insights into the practical aspects of seeking to comply to the plethora of statutes controlling manufacture. Its principal purpose was to review such statutes, and recommend which should remain in force, or be repealed fully or in part. A large number of manufacturers (domestic and factory-based) and master merchants gave evidence on such matters as stamping cloth and the use of tenters to stretch cloth. If you would like more details on the industry in this era, the report is worth reading and is available online.

Crime

Cloth theft, fourteenth century

In 1979, Hanawalt published some revealing work reviewing over 22,000 court cases in the fourteenth century, in eight counties of England (Ref. 18a). She considered: larceny (an illegal act of taking away goods with no claim of ownership); burglary (feloniously and forcibly breaking into a structure and taking away chattels); robbery (theft using violence or a threat of violence to take property from a person). These comprised 38.7%, 24.3%, and 10.5% respectively of all indictments; (homicide was 18.2%).

"Cloth" accounted for 10% of all larceny indictments, 15% for burglaries and 19% for robberies (40% of all robberies were on a highway). Cloth was valuable and was particularly susceptible to robbery, often whilst being transported.

Bloody Code

In 1688, around 50 offences carried the death penalty, but by 1815 this had increased to over 200 (Ref. 19). In 1948, the academic criminologist Sir Leon Radzinowicz took 48 pages of his important book 'A History of English Criminal Law and its Administration from 1750' to list and very briefly describe the capital offences in the eighteenth century, the era (extending into the early nineteenth century) of the 'Bloody Code'. Treason and other crimes against the state were invariably capital since medieval times but the escalation from about 50 offences to over 200 by the beginning of the nineteenth century was swollen largely by acts for the protection of property (Ref. 20).

Larceny

Larceny from a dwelling (burglary) became a capital offence in Elizabeth's reign (18 Eliz. c.7, 1576); the act stated that 'persons being found guilty, outlawed or confessing ... felonious rapes or burglaries shall suffer pains of death'. Those successfully claiming 'benefit of clergy' would be burned on the hand (in later statutes, on the cheek) and may be imprisoned for up to a year.

In 1670, an Act (22 Charles II c.5) declared:

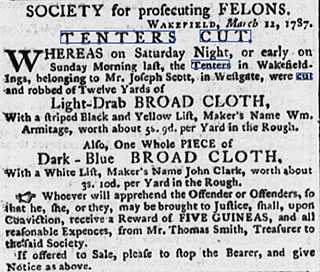

'Many evil-disposed persons have of late more frequently than in former times used and practised the cutting of cloth and other woollen manufactures in the night-time off from the racks or tenters ... and feloniously steal and carry away the same, to the utter undoing and impoverishing of many clothiers, and the great hindrance of the trade of clothing'. And those seeking benefit of clergy shall suffer death in such manner or form as they should if they were no clerks' [i.e. no benefit of clergy; this also applied to those who stood silent, or challenged the charge more than twenty times].

Proof of ownership

In 1825, the eminent legal expert and judge William Blackstone noted that it was difficult to prove the ownership of goods such as stolen cloth or wool (Ref. 21). By 15 Geo II C.27 (1742) dealing with the theft of cloth from tenters in the night-time or theft of wool/yarn left out to dry, the owner, under oath in court, may declare suspects. A constable or other peace officer could enter and search houses and other premises after complaint to justices. If suspect goods were found, the onus with respect to innocence was up to the person found to have them; they had to prove ownership. Failure of the accused to prove ownership in a first offence was a misdemeanour with forfeit and a fine of three times the value, a second offence led to imprisonment for six months and for the third it was a felony, leading to transportation for seven years.

Transportation

There was a provision for judges to reprieve those sentenced to death if they agreed to transportation to His Majesty's plantations overseas (in practice, north America including certain West Indies islands such as Jamaica in this era), for a period of seven years. Those refusing to go, or coming back early would face immediate execution (Ref. 22). Over the period, 1780-1789, for all capital sentences (all crimes) at the Old Bailey, only 44% were executed 36% were transported (to Australia in this period), 7% were freed and just over 2% imprisoned. Thirty years later (1810-1837), only 10% were executed and 77% transported.

In the eighteenth century, larceny was divided into 'petty larceny' for goods 12 pence or under; 'simple grand larceny' included aggravating circumstances and value over 12 pence. It was a capital offence and plainly, valuable cloth either in workshops, on tenters or being bleached on the ground was included, alongside the existing capital offence of burglary for the dwelling-house.

In 1745, 18 Geo II c.27 addressed thefts from place of manufacture and drying grounds for linen, fustian (cotton & flax), callico, cotton, cloth worked. Sentences ranged from death without benefit of clergy, to transportation to colonies or plantations of America for 14 years, at the discretion of the justices. It also applied to those who directly or indirectly assisted the perpetrators.

In 1782, 22 Geo III c.40 covered persons entering by force a house or shop by day or night to destroy serges or woollen goods on the loom or on the rack or damage any rack drying the same, or tools to make. It was a felony without benefit of clergy.

Capital offences were frequently reduced to transportation by benefit of clergy for first time offenders. Most property offences were dealt with by specific statutes that withdrew benefit of clergy. By 1706 persons convicted of common law felony could avoid the death penalty (Ref. 23). Legislation in 1717 (Transportation Act 4 Geo. 1 c. 11) to North America … 'in many of his Majesty's colonies and plantations in America there is great want of servants, who by their labour and industry might be the means of improving, and making the said colonies and plantations more useful to this nation'.

Some statutes that were capital under common law were declared non-clergyable in later legislation. From 1717 most who pleaded clergy were transported to America for seven years (Ref. 23)

A representative case was the trial of Samuel Broughton in December 1736 at the Old Bailey (Ref. 24). He was 'indicted for cutting and stealing (with Joshua Broughton, not taken,) two Yards and 3 qrs. of Woollen Cloth, value 30 s. Feb. 11, about the Hour of Twelve at Night, from certain Racks and Tenters in the Parish of St. Leonard Shoreditch ; the Goods of Gabriel Fowase. Guilty, 4 s. 10 d.'. He was accused of two further thefts and cutting of cloth on tenters.

He was found guilty of the three offences and sentenced to be transported. (In that court session, 11 were sentenced to death, five to be burnt in the hand, and 51 to be transported, for a variety of crimes) (Ref. 25).