On this page...Tenter-banks|Place names|Historical vistas|Travellers|'On tenterhooks'|.

In the scenery

Tenter-banks

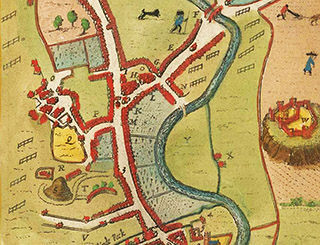

Examples of tenter-banks are shown throughout this website. Good examples of banks on level ground are those supporting the tenters of Roads Mill near Wardle, Rochdale (below). Note how the slightly elevated bank is devoid of rushes, being dryer than the surrounding land. Some of the post-holes for the tenter supports are still present atop the banks. The remains of the mill are now under Watergrove Reservoir but the elevated tenter-fields survive on a plateau above.

Left - A tenter-bank near Roads Mill (fullers), Wardle. On the right is the 1850s 6-inch OS map showing the mill and associated tenter-fields. The red 'T' shows the approximate location of the photo, looking west.

There is a rationale for having tenter-banks on notable hill slopes: to provide level platforms around contours. What is the point of elevating the tenters a little distance in a level field? Rather like the use of props to elevate household washing into the breeze, even slight elevations can have benefits in increased wind-speed, particularly over rough ground like moorland. Very close to the uneven, vegetation-laden surface, the wind speed is very low. Another explanation could be the erosion in wet soft ground near upland mills from the foot-fall of tuckers in mounting and dismounting the cloth fom the tenters over many years. The bank would be the original ground level, above the eroded wet paths either side of the racks that would promote rushes in later years.

Place names

Reminders of the ubiquitous tenters in woollen cloth-making areas are the field-names of enclosures and other landscape features of tenter use. Amongst these are close, croft, garth, room, hey, hill, balk, field etc. (Ref. 1). Tenter Hill is relatively common place name, marked on Ordnance Survey maps to the present day (unlike field-names). There are a number of streets that include 'tenter' in their name. Nineteenth century tithe maps and apportionments do however, note field-names.

Tenter Hill in Slaidburn. Accounts from 1422-3 mention a fulling mill in the village, and a corn mill (possibly housed in one building with two functions). The mill was probably on Croasdale Brook, in the valley below the hill (right of image, within trees). Some locals say they have identified tenter-banks on the hill. I haven't.

A review of the tenter associated field-names in the Leeds Metropolitan District was undertaken. The 'Tracks in Time' website was employed to view tithe maps and apportionments (a facility now removed by the West Yorkshire Archive and replaced with the 'West Yorkshire Archive Service Tithe Maps' website, Ref. 2). The maps and apportionments were dated 1839-50 from 10 parishes in Leeds. There were 11 -garths, 40 -crofts, 42 -closes, and nine -hills. Of the 98 tenter names (some had multiple names e.g. Tenter Hill Close), 65 were now built over, 20 were still open pasture, nine partially built over, and three miscellaneous e.g. a golf course.

Left - 'Tenter Heys' field in Grindleton 1807 (formerly West Riding of Yorkshire) (Ref. 2b). Historically, there may have been a fulling mill on Grindleton Brook, near the quarried hollow and the footbridge (top left). 'Hey' as a field-name in this context denotes an enclosure. Right - View of the tenter-field with a probable tenter-bank, south facing (marked).

Historical vistas

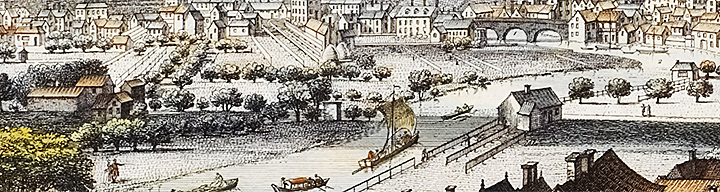

A few examples are shown here of historical vistas that included tenters. Samuel Buck (1696-1779), and his brother Nathaniel, were renowned for engravings of historical buildings such as castles, monasteries and townscapes. They were Yorkshiremen. His engraving of Leeds in 1745 shows many seams of tenters at the Aire riverside, and also adjacent to housing and workshops.

Tenters in Samuel Buck's 'South East Prospect of Leeds', 1745.

In Leeds, antiquarian Ralph Thoresby's major work on the history of Leeds (Ducatus Leodiensis, 1715) includes a vista, 'The Prospect of Leeds from the Knostrop Road' by Francis Place. Many tenters (and some fences) are shown near St. John's church, founded by wool merchant John Harrison in the 1630s.

Detail from 'The Prospect of Leeds from the Knostrop Road' by Francis Place. The church is St John's.

Stroudwater in Gloucestershire was a notable centre for the production of cloth. Dyeing was its speciality as the wonderful colours on the tenters above the village testify.

'View of Wallbridge' c. 1785; artist unknown. Stroudwater Scarlet dyed cloth on tenters above the village. Lower image is a detail of the tenter-field. Courtesy and copyright Museum in the Park, Stroud.

Tenters in the mill yard at Stanley Mill, constructed in 1813 around a 'fireproof' iron frame. It was one of the largest mills in Gloucestershire.

Stanley Mill, Ryeford, Stroud, artist and date unknown. Courtesy and copyright Museum in the Park, Stroud.

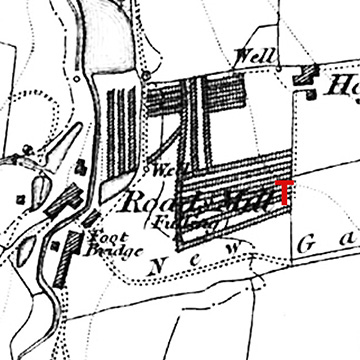

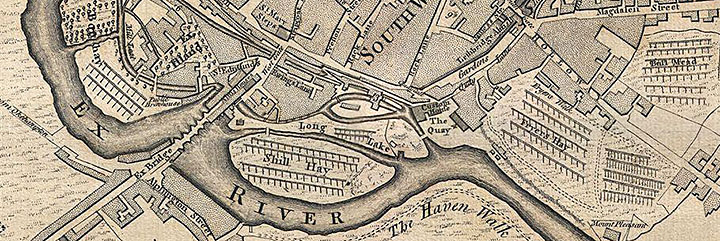

Exeter was a prominent cloth-making city and Donn's map marks many tenter-hays.

Tenters in Exeter near to the River Exe and leat in 1765, associated with fulling mills. From a map surveyed by Benjamin Donn, 'A Map of the County of Devon, with the City and County of Exeter', Source - Ref. 16.

Travellers

The industrial revolution had its initial impact on the countryside, taking advantage of the fast-flowing streams to drive water-wheels. This transformation divided commentators and travellers. Not all welcomed it. In 1838 on his travels to identify the remains of rural life, William Howitt bemoaned the tall chimneys of 'vast and innumerable factories' that had transformed the life of rural children from a simple idyll in nature to the 'capture and confinement of these little English savages in the night and day noise labour and foul atmosphere of the cotton purgatories' (Ref. 2a). To others, the labour in the countryside brought benefits - employment and pleasing vistas of new trade - in the juxtaposition of manufacture and countryside.

In the 1720s, Daniel Defoe published an account of his tours in Great Britain. On his journey over Blackstone Edge from Rochdale (Lancashire) to Halifax he noted features of the domestic woollen industry approaching Sowerby along the Ryburn valley and in the environs of Halifax (Ref. 3):

The sides of the hills, which were very steep every way, were spread with houses … the land being divided into small enclosures … every three or four pieces of Land had a house belonging to it … we could see that almost at every house there was a tenter, and almost on every tenter a piece of cloth … from which the sun glancing … shining (the white reflecting its rays) to us, I thought it was the most agreeable sight that I ever saw, for the hills … rising and falling so thick, and the valleys opening sometimes one way, sometimes another, so that sometimes we could see two or three miles this way, sometimes as far another … we could see through the glades almost every way round us, yet look which way we would, high to the tops, and low to the bottoms, it was all the same; innumerable houses and tenters, and a white piece upon every tenter.

The manufacture of woollen cloth in the West Riding in the early eighteenth century was undertaken largely by independent clothiers, the trade ranging in size from single families working at home to more entrepreneurial clothiers with a number of widely dispersed spinners and weavers in the countryside. The clothiers arranged the fulling and tentering of the piece, which was then sold in this 'balk' state in cloth halls and markets to merchants, who arranged the finishing. The enclosures were used to support a horse and undertake agricultural activities such as growing food, keeping pigs, hens etc.

Left - Clothiers taking their pieces to the cloth hall on their overloaded Galloways. Right - The 'coloured' cloth hall at Leeds (there was another cloth hall for white cloth). The hall opened one hour only on Tuesdays and Saturdays for the clothiers to display their wares on stalls for the merchants to peruse. From Walker G, 1814, The Costume of Yorkshire.

Defoe was not alone in his appreciation of the visual impact of tenters on valley sides. Thomas Carlyle in his account of the national character in the times of James I and Charles I wrote (Ref. 4):

Certainly the Cloth-manufacture does thrive. In Stroudwater and the Western valleys [Gloucestershire], white woollen webs … stretch openly on tenterhooks; a goodly spectacle, as you issue from the Cotswold Hills.

On a journey in 1769 between Keswick and Kendal, poet and travel writer Thomas Gray noted (Ref. 5):

I enter'd Kendal almost in the dark & could distinguish only a shadow of the Castle on the hill & tenter-grounds spread far and wide round the Town, which I mistook for houses.

A 1725 'tragi-comedy' written by 'a gentleman in Gloucestershire' extolled (Ref. 6):

At my entrance into your County, casting my Eyes from the Hills to behold your pleasant Vale, I view'd on my Right Hand the Cloth-Racks at Chalford, in their glorious Colours of Scarlet, Crimson, Blue and a variety of other delightful Colours …I was fill'd with Admiration and certainly thought I was now come into the Land of Canaan, believing it not to be equall'd by any part of the World.

Samuel Rudder in his 1779 'A New History of Gloucestershire', (Ref. 7) commented on the local vistas around Stroud. From Rodborough Hill SSW of Stroud:

There is a large tract of rich country in the fore ground of the landscape, interspersed with good houses, gardens and highly cultivated plantations and inclosures; and these are improved with the beautiful colouring of clothes on the tenters, accompanied with a variety of other objects, peculiar to a clothing country. Here the fancy glows and agreeable ideas rise of the benefits and extensiveness of trade and manufactures.

A great number of well built houses, equal to a little town, lying very contiguous, but not joined together. They are intermixt with rows of tenters, along the side of the hill, on which cloth is stretched in the process of making. This variety of landscape is uncommonly pleasing.

The intermixture of gently rising hills and dales, with woods and lawns, produces in this country a great variety of pleasing landscapes and prospects, still heightened and improved by the beautiful tints of fine woollen clothes stretched upon the tenters.

On his visit to the fulling mills in Exeter in 1754 (Ref. 8), the Swedish industrial spy Angerstein noted that:

[Cloth was] 'pounded and washed, after which it is fastened to frames for drying. With their many different colours they contribute to the beautiful view from the promenades, in addition to the other attractive sights'.

'On tenterhooks'

Vertical hooks with shanks embedded in the wooden bar.

The sizes, spacings on the bars, and specific designs of iron tenterhooks were dependent on local manufacturers and cloth type. In general they were 'L' shaped with tapering shanks and hooks. Goodall (Ref. 8a) sketched various shapes of the hooks, sizes ranged from 18-39 mm and shanks 20-51 mm in length.

Tenterhooks were usually made of bare iron but some clothiers employed enhanced versions. In 1762, John Brearley, a cloth frizzer, noted that (Ref 9.):

[Mr Lumb, a dyer at Wakefield Bridge] keeps tentering and teeming on a Sunday all day long ... on a fine day gett 60 or 70 pieces drye ... His tenter hooks are all tined and the will not rustey and are done for one peney a hundrd and itt makes them sliperey and keep theire sharpness and good to tenter on.

('Teeming' was to moisten dry tentered cloth by say, laying it in dew on the ground; this improved the feel of the cloth ('handle') before sale and could facilitate further finishing processes).

Early examples of the word 'tenterhooks' arise in the 1480 Wardrobe Accounts of Edward IV. Ironmonger Piers Draper charged 2 p for 100 'tentorhooks'. Accounts are also shown for 200 'tentourhokes' delivered for the visit of the 'Duchesse of Bourgoine' and used with 'crochettes' (forked/hooked supports, probably for wall hangings, not drying cloth) (Ref. 10). The accounts of George Kirk, mercer, in 1490 in York mention the procurement of 'tenterhukes' for chapel hangings (Ref. 11).

Tenterhooks excavated from Jamestown, Virginia, the site of the first permanent English colony. The archaeologists classify these as made in England in the early seventeenth century. In the American context, they were likely to have been also used to stretch skins. Photo courtesy of Jamestown Rediscovery, taken from 'Jamestown Rediscovery - Historic Jamestowne, Archaeology'.

Tenters strain cloth, which requires tension, and in poor weather the piece may have to be mounted taut for prolonged periods. It is not surprising that over the centuries, the widespread use of tenters with hooks under strain has been applied to human conditions. For example, the OED defines the common expression 'to be on (the) tenterhooks' as in a state of painful suspense or impatience.

An early example of the association of tenters with stretching is 1551 when Thomas Cranmer (Archbishop of Canterbury) preached that 'Papistes...set Christes wordes vpon the tenters, and stretched them out so farre, that they make his wordes to signifie as pleaseth them, not as he meant.' (Ref. 12).

In 1594, a letter from the 2nd Earl of Essex to Sir Henry Unton (Ambassador to France), discussing a request for assistance, explained a dilemma he had 'which is as much as my wit and credit both set on the tenter hooks can stretch to' (Ref. 13).

An early example of 'on tenterhooks' is from 1596. In the Anglo-Spanish war (1585-1604), Cadiz was captured and sacked in that year by a Anglo-Dutch joint operation on the ground led by the 2nd Earl of Essex. Agustino Nani, the Venetian Ambassador in Spain, wrote to the Doge and Senate on 23 July 1596 (translated thus) (Ref. 14):

The English fleet, after leaving Cadiz, was compelled by the weather to return to within sight of that city, where every one was on tenterhooks to know when the weather would let them sail.

This is the earliest use of 'on tenterhooks' found by the website author (note the caveat in the reference below).