RESTORATION OF OTTERBURN MILL TENTERS: The photograph above of the field tenters at Otterburn Mill was taken in September 2017. Unfortunately, the site was flooded in 2019 and 2020 and the tenters were damaged. The National Lottery Heritage Fund awarded £85,158 in November 2023 to the mill to restore the frames, in association with several heritage organisations and individuals.

In mid-June 2025, it was announced that Otterburn Mills Limited had gone into voluntary Liquidation, with the loss of 28 jobs, and had ceased trading. My understanding is that the site, including the tenters, is not open to the public.

Introduction

Purpose of field tenters

Field tenters - commonly called 'racks' in the south of England - were used to dry and stretch woollen cloth in the open air as part of the 'finishing' process during manufacture. Tentering was an essential part of finishing to meet breadth and length requirements, align patterns, remove rucks etc. Tenters were deployed in rural and urban areas by both individual clothiers and fullers in the domestic industry, and within the factory system. They were visually striking in the landscape of woollen cloth-making districts, particularly when the cloth had been bleached, dyed, or was patterned.

In England, field tenters have now completely disappeared (bar one set), but leave evidence such as place names and the slight remains of groundworks like tenter-banks. These were narrow level earthworks, sometimes revetted, to provide a stable platform around the contours on hill slopes. Long linear mounds were occasionally used on level ground to elevate the tenters into the breeze.

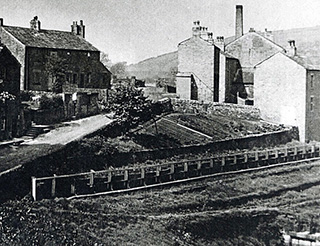

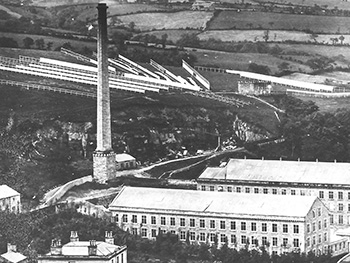

Stubbins Vale Mill, Rossendale, Lancashire c. 1870. Tenters are on the hillside, above the mill in the valley. Courtesy of John Simpson, Helmshore.

'Steps near Honley' painted by Thomas Beaumont, 20 July 1829, and recently rediscovered. Detail - tenters in Steps village, West Riding of Yorkshire. Copyright a private collector, used with permission.

JMW Turner, 'Leeds', 1816, detail - dyed cloth on tenters, Beeston Hill, Leeds. Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art.

Circa 1840 stone tenter posts, Wall Hill, Dobcross, West Riding of Yorkshire, with slots for wooden horizontal beams holding tenterhooks (now gone), the lower set adjustable in height for various cloth widths and adjustment for width when stretching.

Larger versions of these images are available in the Gallery of the Modern Remains page.

The two principal types of woollen textile were 'woollen cloth' and 'worsted'. In general, only the former was fulled and stretched on tenters. The woollen web from the weaving loom required finishing to make woollen cloth serviceable. This initially included 'scouring' (washing to remove natural dirt, manufacturing oils etc.) and fulling (milling/felting) to consolidate the piece prior to raising and cropping a nap to give a good finish. Scouring and fulling were wet processes that led to substantial shrinkage and distortion of the cloth. It then required stretching and aligning on tenters to make it functionally useful and commercially attractive.

Tenter misuse

The shrunken piece was susceptible to deliberate excessive stretching on the tenters, largely for commercial gain and efforts to meet width requirements, the latter particularly problematic with poorly prepared yarn, or badly woven, or imperfectly fulled textile. Overstretching legal cases extend back to at least the medieval period - an amercement (fine) was payable to the Exchequer in 1202/3 by some men of Ashbourne (Derbyshire) for overstretching cloth (Ref. 1).

Tenters in Batley, West Riding of Yorkshire, c.1850. The town was within the 'Heavy Woollen District' where 'shoddy' and 'mungo' were manufactured from reclaimed waste woollen cloth, rags etc. Single tenters, probably of individual clothiers, and the multiple tenter 'seams' of the factory system are evident.

Defects in the cloth arising from overstretching could be illicitly disguised prior to sale by using inappropriate materials such as waste wool, oatmeal and chalk. These deceitful practices inevitably came to light for customers when notable shrinkage occurred in tailored garments in the first shower of rain, and holes appeared in overstretched areas.

For centuries, legal statutes and the requirements of local trade bodies (guilds) were employed to prohibit and detect such malpractices; they brought the quality of English woollen cloth into disrepute, to the detriment of the local and national economies, and the nation's reputation abroad.

'Tuckers' mounting blankets to a fixed width on field tenters in Witney in the 1920s. The 'stockful' the men hold (the load from one fulling stock) contained about 12 blankets in a single strip. They were bleached just before tentering either by laying on grass in sunlight, or using hydrogen peroxide in bleaching sheds. Courtesy Oxfordshire County Council - Oxfordshire History Centre.

Valuable cloth on tenters in the open (and indeed within workshops and dwellings) was also susceptible to theft. This was a felony in some centuries and a capital offence. Notwithstanding a sentence of death, in practice, executions for cloth theft were uncommon in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Transportation to the colonies for 7 or 14 years or branding were employed.

Drying problems

Poor drying weather was a persistent problem. This led to the growing use of indoor heated 'stoves' or 'dry-houses' in the factory system from the early nineteenth century (facilitated by the availability of steam power). Expensive and complex 'stenters' that mechanised drying and stretching to a fixed width were introduced from the mid-nineteenth century. Outdoor tenters persisted in some parts of the trade into the mid-twentieth century, such as blanket-making. Even in the era of widespread heated indoor tentering, field tenters were often retained as a more economical approach in good drying weather.

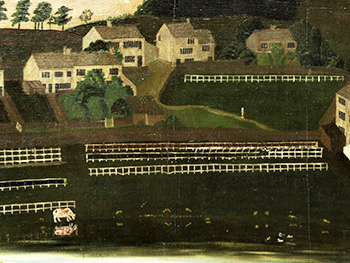

'View of Wallbridge' c. 1785, artist unknown. Detail - tenters on the hillside above the village, some with cloth dyed 'Stroudwater Scarlet', used for military uniforms. The area was renowned for its dyeing. The vistas of such tenters on hills in England were favourably commented upon by travellers. Copyright 'Museum in the Park', Stroud, Gloucestershire. Also visit the Stroudwater Textile Trust.

Control measures

It is evident that open-air tentering was frought with technical and practical difficulties, compounded with the risk of malpractice, and the required adherence to statutes and local practices to meet quality and size standards for the cloth. This was policed by appointed officials such as alnagers, searchers, stampers and inspectors with, in some eras, powers of entry to homes, workshops and tenter-fields.

The control measures employed over the centuries included, for example:

- the requirement to set all tenters in open spaces for inspection, not kept indoors or inaccessible;

- stamping of wet, fulled cloth with the names of the maker, miller and the dimensions;

- re-wetting tentered, dried cloth ('troughing') thereby revealing the inherently stable true dimensions, and detecting the magnitude of overstretching;

- aspects of tenter construction such as requiring a fixed lower bar to constrain stretching, prohibiting winches to stretch the cloth longitudinally, and marking tenter racks with dimensional scales to compare the stretched length of the piece to the dimensions on the stamper's or miller's legal stamp.

There were even attempts by the Crown in 1597 to prohibit stretching 'Northern Cloths' altogether, an essential process in the manufacture of woollen cloth. Unsurprisingly, the prohibition was generally ignored, particularly in Lancashire.

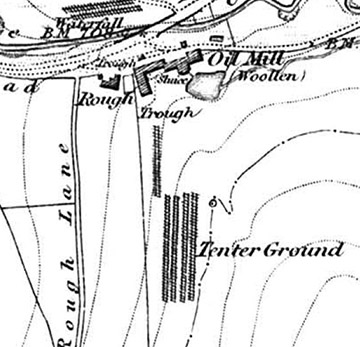

The tenters of the 'Oil Mill' woollen mill, Lydgate near Littleborough (Lancashire), just off the old packhorse road to Halifax (West Riding of Yorkshire). Left - tenters depicted on the 1840s OS 6-inch map. Centre - the remains of the lower set of tenter-banks on modern aerial photographs (the parallel lines in the centre of the image). Right - the remains of two of the tenter-banks on the ground (marked). Aerial photography is the best way to identify tenter remains; their identification on the ground without this evidence or mapping is invariably difficult.

Overview of field tenter design

Tenters comprised two lengthy horizontal wooden beams set apart vertically, each with embedded sharp tenterhooks to attach the cloth. The lower and upper beams were supported by wooden, metal or (less commonly) stone vertical posts. The tenterhooks were fitted into the lists (selvages) of the cloth.

There was a facility to vary the vertical separation of the two horizontal sets of tenterhooks, usually by displacing downwards and clamping the mobile lower beam, thereby stretching the cloth uniformly to the required width. The upper beam was usually fixed. A mobile lower beam also enabled the safer extraction of the taut, dry cloth from the sharp hooks. Some types of tenter also had a facility to stretch the cloth horizontally in length using, for example, a winch on a vertical beam with tenterhooks to grip the end of the piece (the 'head').

Tenters could extend to over 100 yd (91 m) in length, the height (to accomodate the cloth width) determined by the local specialities in manufacturing i.e. woven on either narrow or broad looms, resulting in finished cloth up to about 52 in (1.3 m) wide or to about 72 in (1.8 m) in width respectively (even wider on the looms to accomodate shrinkage from fulling). In the extreme, tenters could be up to 12 ft (3.7 m) high, those for blankets being a common example.

This website...

Four further pages are available:

- Cloth Making - the stages of woollen cloth manufacture; fulling and the requirement to tenter cloth; cloth shrinkage after fulling; weather and tenter use outdoors; 'wet-houses'; indoor tentering; provision of tenters to domestic cloth-makers.

- Statutory Control - Local rules and statutory acts to control woollen cloth manufacture; scourge of overstretching cloth and other deceits; steps taken to address cloth theft from tenters.

- In the Scenery - The siting of tenters and tenter-banks; place names; depiction of tenters in travel accounts, art, maps; use of the idiom 'on tenterhooks'.

- Modern Remains - Survey of historical field tenter remains in Lancashire and the West Riding of Yorkshire; examples employing historical mapping, aerial images and photographs; gallery.